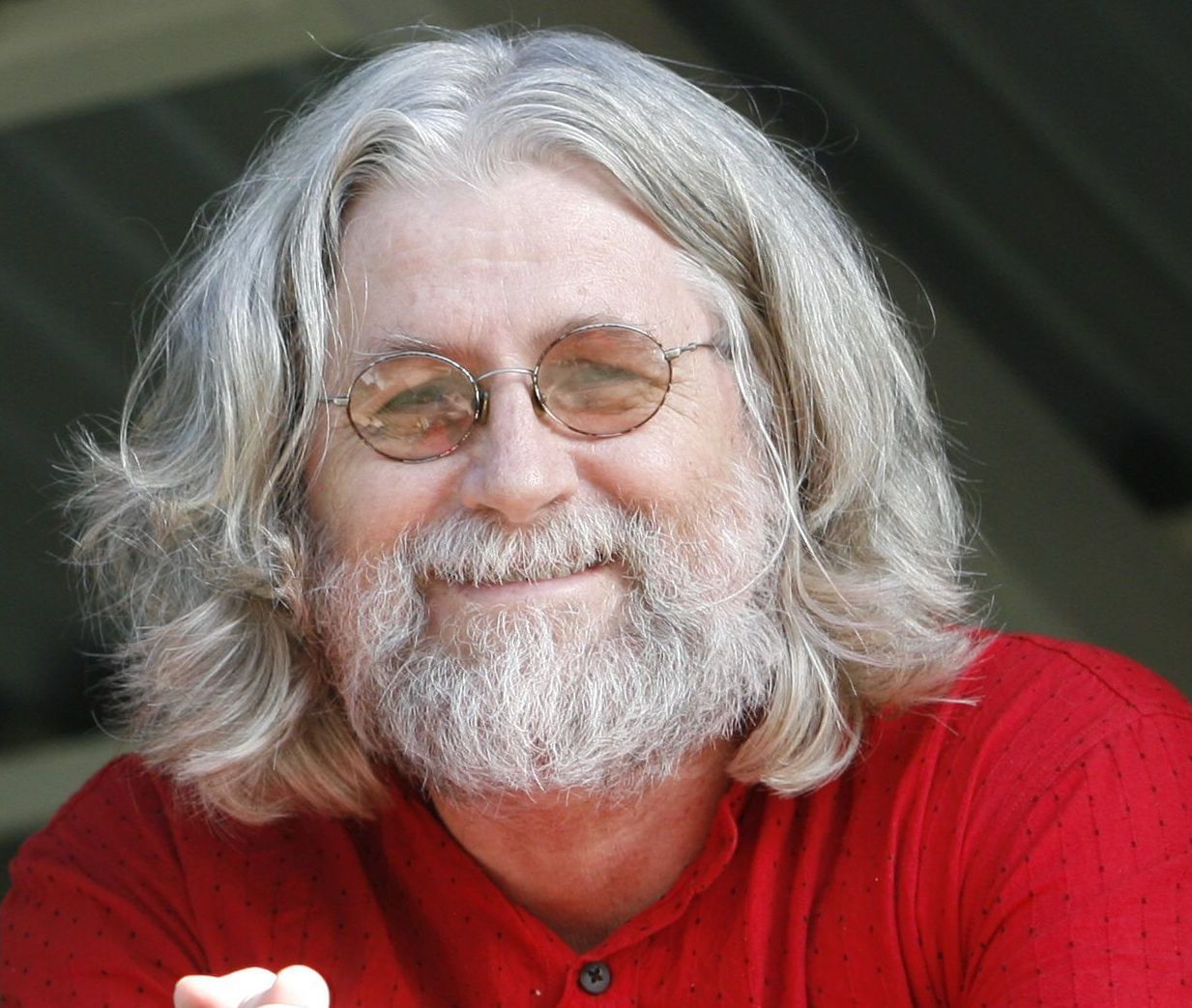

Long-term Westender contributor Dave Andrews reminisces about an unusual Christmas celebration.

Long-term Westender contributor Dave Andrews reminisces about an unusual Christmas celebration.

In India, Christmas is called Burra Din or the Big Day. How do you celebrate a Big Day like Christmas in a country like India?

We lived in India for twelve years, doing community development work with marginalised people in New Delhi. And I will always remember one year sitting around, drinking chai with friends, and discussing how we would do Christmas.

We were living in a multi-faith community at the time. With a dozen Protestants, half‑a‑dozen Catholics, a few Orthodox, a bunch of Hindus, a couple of Muslims and a Humanist. And everyone got involved in the discussion..

The popular Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox ways of celebrating Christmas seemed embarrassingly inappropriate in the light of the Hindu insistence on spirituality, Muslim concern for purity, and Humanist commitment to relevance.

We were determined to discover a way, which we could celebrate the Big Day, that would get beyond the narcissistic frenzy of stuffing our faces and setting ourselves adrift on a sea o f booze. But we really didn’t know what to do.

After much discussion, we all agreed on three ideas that we thought might be worth a try.

He first idea was to give a gift to God. As the magi did at Christ’s birth. To give something of ourselves, something that was precious to us, a part of ourselves, as our offering of gratitude and thanksgiving. The second idea was to give gifts, anonymously, to our neighbours. As Christ had told his disciples to do. To give to others without expecting anything to be given in return. The third idea was to throw a party for the people who never got an invite to a party. Along the lines Christ advocated, when he said, ‘if you have a party, do not invite your friends, or relatives, or your rich pals. But, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind!”

We began the Big Day with a special community service. In which each of us gave a gift to God. One person after another stepped forward and presented their gift. One offered a song they had composed for the occasion; another a poem they had written; and another a prayer. One person promised to do the washing up in the community for a week. Another, who had thrown his weight around, promised to work through his anger more constructively in future.

After the service we dispersed to distribute gifts to our neighbours. Someone gave away a beautiful picture they had painted. Someone gave away a colourful bunch of flowers they had arranged. And someone else gave away a delectable cake they had baked. Later that day I ran into knots of people round the neighbourhood – barely able to contain their joy – out on the streets, raving about the surprise gifts that they had been given anonymously.

After we had shared our gifts, we gathered together in the community house to finish the preparation of our midday meal. It was a sumptuous feast of Hindusthani delicacies: curry, biryani, puri, rice, raita and acchar. And when it was ready we went out to invite our guests.

There were Rajasthani labourers across the road who were working at a building site. There were beggars round the corner. There was a man with elephantiasis who hobbled along on his crutches. And there was a boy who everybody said was crazy.

We all sat down to enjoy the meal together, various ones of us taking turns to serve our guests. For the ‘high caste’ among us to have invited the ‘low caste’ Rajasthani labourers and the beggars on street corner to dinner was breaking a taboo. They knew the risk we were taking in breaking caste ‑ we may ourselves be treated as ‘outcaste’.

But it was not so much the taking of the risk of breaking caste that impressed them. It was the fact that we actually shared a meal – together – as equals. They had expected us to give them a meal, but to eat and drink separately.

They were shocked when we sat down next to them and began to eat and drink with them. It took quite a while for them to adjust. But gradually they did. Soon they got into it. Tales were told, stories were swapped, jokes were traded back and forth. And laughter broke down the walls of years of alienation. The Big Day had arrived – it was Christmas.