One year ago this week …

This week marks one-year since West End’s last major flood. It has been 12 years since the 2011 flood, 49 years since the 1974 flood, 130 years since the 1893 flood, and so on. Floods, a term used to refer to nature’s impact on human settlement, have happened here since immemorial.

Westenders are still learning, debating, preparing (and perhaps despairing) in the lead up to the next major flood event.

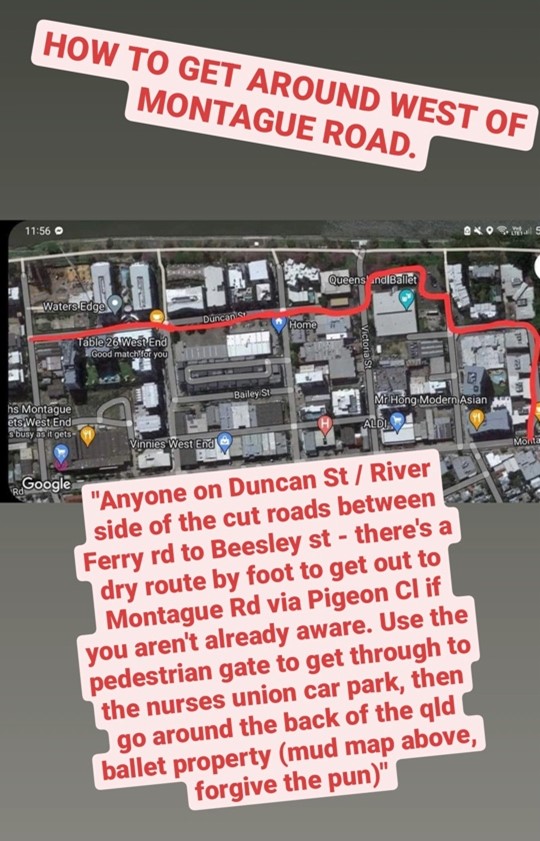

As a community volunteer (I joined the WECA board in late 2021), I was amazed by the pace at which community leaders and longstanding residents sprang into action as the 2022 floodwaters drew closer. Countless emails, text messages and social media posts flew around West End networks, responding to the immediate needs of flood-affected locals and organising resources, accommodation, food, and communications. Not to mention all the unrecognised instances of neighbours helping neighbours.

This grassroots flood response is an experienced, well-oiled machine. People know each other here. Many have been through a flood before and know what needs to be done to service community issues when they arise.

Community as first responders

Rapid and effective community response to disaster is not unique to the Kurilpa neighbourhood. It is an innately human experience shared by resilient communities at risk everywhere.

First Nations first responders and volunteers from Lismore-based Koori Mail newspaper were operating recovery centres less than a week after the February 2022 floods. In the months following, they pivoted into a flood hub, providing clothes, counselling, food, supplies and financial support to flood survivors.

Further afield, residents of Loíza in Puerto Rico, led by the women of NGO Taller Salud, demonstrated dramatically innovative responses to loss of power, food, energy, and reconstruction following the deluge of Hurricane Maria in 2017 and Hurricane Fiona last year. From these localised experiences, they designed useful tools to guide residents in future weather emergencies.

Rising flood knowledge

Here in Kurilpa, we too have a wealth of innovative knowledge accumulating with each flood experience. Our collective memories of 2022, 2011, and even earlier, are a vital source of knowledge for preparing, responding and recovering from floods. They also allow recognition and learning about what our community does each time floods occur.

After the 2022 floods, I heard numerous flood stories and lessons shared in cafés, dog parks, street corners and online forums. Knowledge sharing flourished with the formation of Resilient Kurilpa and the community consultations that followed.

For instance, a costly lesson was shared by apartment dwellers from Riverpoint Apartments about securing lifts in case the basement flooded, potentially saving body corporates thousands in the next flood.

Others suggested filling a bathtub in case water supply is closed off, leaving a key to basement storage with a trusted neighbour in case your out of town, and referring to inclusive emergency planning resources in flood mitigation planning.

Historical knowledge is circulating too, with the extensive research of Dr Margaret Cook unsettling colonial values of progress and development on a floodplain. There are valuable lessons here. For example, the seductive promise of riverfront property investment and city centre development in South Brisbane was washed away in the 1893 floods. In its wake, Orleigh Park was formed after two years of community petitioning the South Brisbane Council to resume the land.[1]

Cultural knowledge also plays a vital role in reframing dominant ways of understanding and managing extreme weather events. After the 2019/20 Black Summer Bushfires, renewed energy surrounded Indigenous fire and land management experts like Victor Steffensen of Firesticks Alliance. In his 2020 book Fire Country Steffensen writes, “Applying knowledge learnt from country is how Aboriginal people strengthened their wisdom to live sustainably for thousands of years”.[1] Traditional knowledge should not simply be archived in databases, he says, it should be installed into people, shared in practice, with young people and on country.

Collecting knowledge (and funds) for the Kurilpa Flood Library

Floods will happen again in Kurilpa. Next time, new people will be impacted. Though with time passing and other pressures rising, the urgency of flooding wanes. Resilient Kurilpa members, and many flood-impacted residents, remain active in the flood space.

With the support of Resilient Kurilpa, I’m launching a crowdfund campaign to raise $10,000 to build the Kurilpa Flood Library.

The library will collect and catalogue local, historical and cultural flood knowledge, stories and lessons from Kurilpa residents, to use in our planning and share with our children, new neighbours, visitors, building managers, and decision-makers.

The funds will allow us to build on Resilient Kurilpa’s flood toolkit website by packaging flood knowledge in an accessible, beautiful, and free website, with illustrations by local artist Maeve Lejeune (Houses of West End). The website will host free printable tools and resources designed to support flood knowledge sharing in workshops and engagements with various groups in our community, like schools, NGOs, and residents.

Community crowdfunding enables the Kurilpa Flood Library to be supported by the people who contribute the stories and benefit from the knowledge.

For the years (and floods) to come, the Kurilpa Flood Library will provide a place where people can visit, read our stories, and learn about flooding on the Kurilpa Peninsula.

Support the Kurilpa Flood Library by donating at Gofundme.

Follow Resilient Kurilpa on Facebook for updates on the knowledge collection process and crowdfunding.

Notes

[1] Steffensen, V. (2020). Fire Country: How Indigenous Fire Management Could Help Save Australia. Hardie Grant p108.