Evelyn pointed . . . Over there — the Uffizi Gallery, a showcase for men. History has erased the unseen, said Evelyn. And we will never know the contribution women made to that unique time . . . So where were the women? . . . Inside mostly, if you were wealthy and married. Considerable time in the birthing room, hoping to produce male heirs . . . Organising the servants. Sewing. Making bread . . .

The wise words of Evelyn Skinner — a key protagonist in Sarah Winmans’ lovely novel Still Life and my summer read — speaking to us from the early 1950s. While Evelyn is a fictional commentator there would have been women like her around when I went to art school in Adelaide in the mid-1960s, but we weren’t listening. In my experience voices like hers were not heard for another decade.

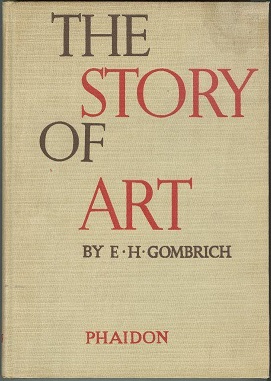

What we heard was the clear 1950s Western-male voice of Ernst Gombrich in The Story of Art. Every art student had the book. Gombrich’s writing was conversational and intimate and more than 8 million copies were sold. The first two sentences became famous: ‘There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists.’ Criticism emerged however, about the book’s unenthusiastic approach to contemporary art and its complete omission of female artists with none included in the first edition in 1950 and just one in the 16th edition in 2022. The Story of Art maintained the masculine artist-as-hero myth. We needed you Evelyn.

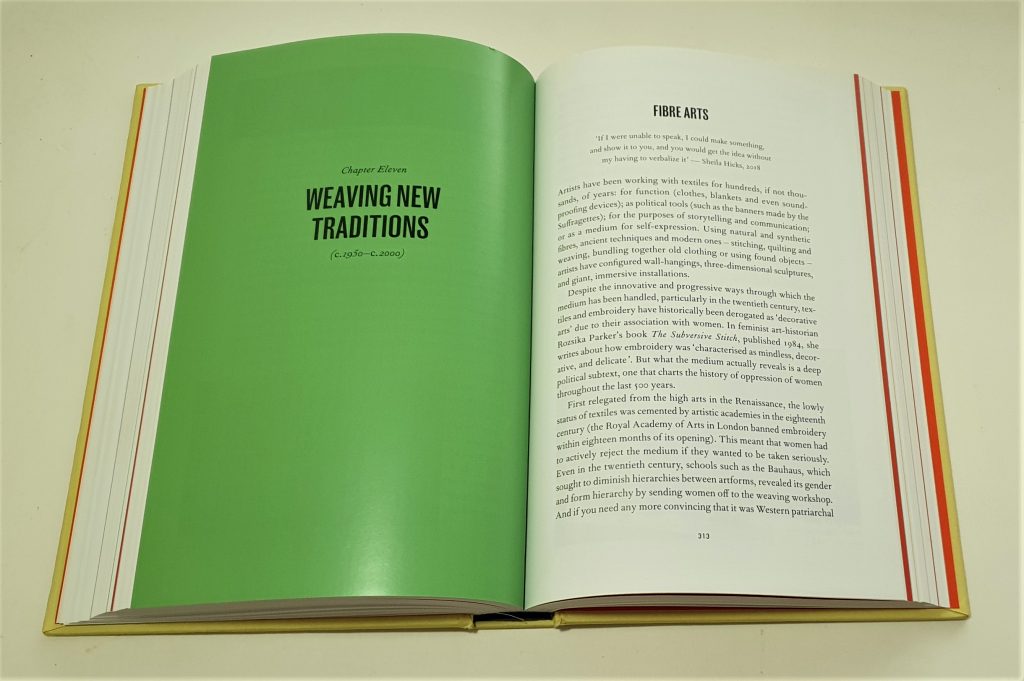

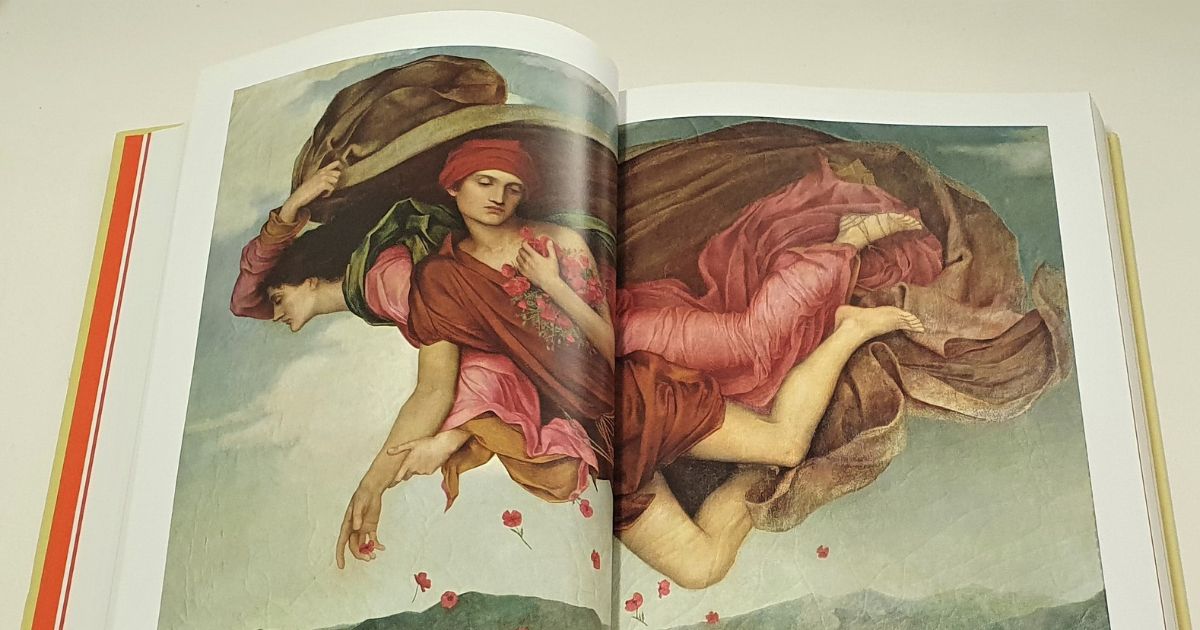

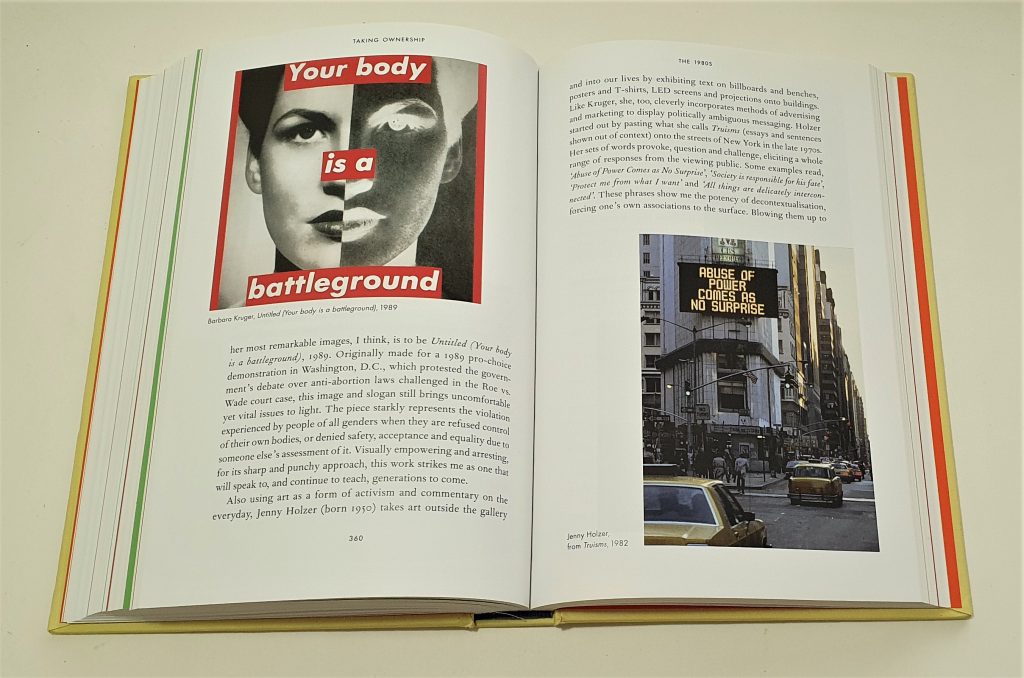

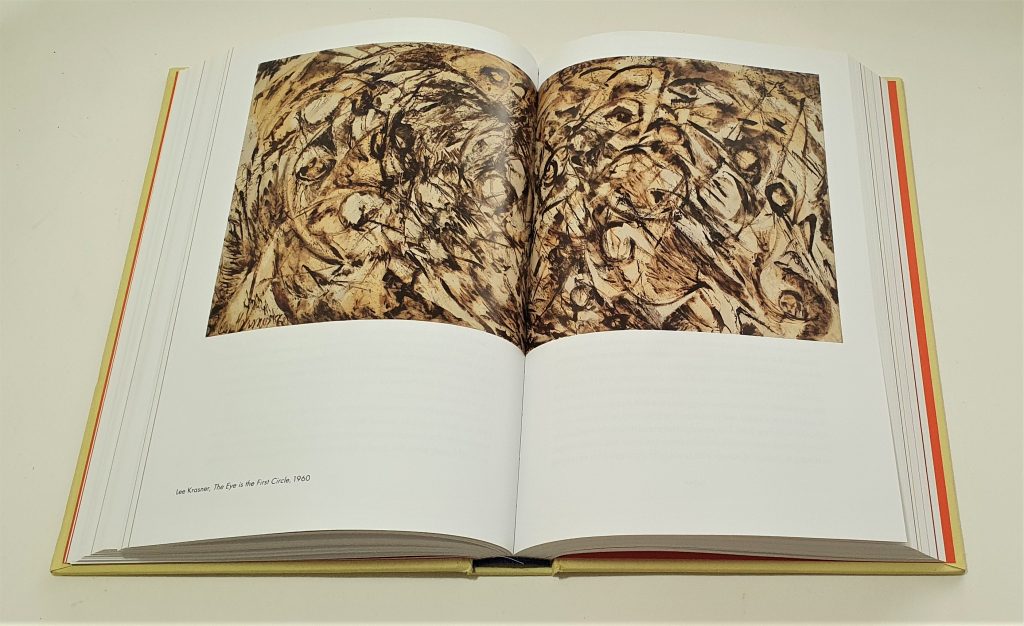

And now, 70 years on, with the stated intention of offsetting the emphasis on male and Western works in Gombrich, British curator and art historian Katy Hessel has responded with a book of more than 300 art works by a multitude of international female artists titled The Story of Art Without Men, published in late 2022. It’s an accessible book celebrating 500 years of art production by women, impressively written and presented. ‘I am looking to breakdown the canon I have so often been confronted by in the culture in which I have grown up’, says Hessel. And so she goes and does it brilliantly, in ways both oppositional to, and parallel with, Gombrich.

Hessel, however — within the confines she has set herself — is totally inclusive of a broad range of art practice including and focusing on modernism, the body in art, weaving and quilting, photography and text, decolonising narratives and reworking traditions. It’s encyclopaedic in its coverage of artists, many of whom by now are renowned in the art world, with some having been highly respected since the 70s. Sadly but unsurprisingly, I could only find reference to one Australian artist, Emily Kame Kngwarreye.

Hassel’s book is marketed as correcting the omissions of decades inferring that little has been published in the intervening years to remedy the bias. Not true of course. Linda Nochlin’s game-changing essay of 1971, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists’, explored the institutional obstacles that prevented women in the West from succeeding as artists. Since then her compelling text has been reprinted regularly including in Women Artists: The Linda Nochlin Reader, 2015, edited by Maura Reilly. And just briefly mentioning one other publication, Marilyn Stokstad’s Art History (1995) — the book of choice for a post Gombrich generation of teachers and students — presented a broad view of art in a sympathetic manner and included women and the arts of many continents and regions.

We hear you Katy Hassel, Linda Nochlin, Evelyn Skinner and the others.