Lots of very strange things have been happening around the world since the Covid lockdowns started, but probably no-one expected that a song written in the 1860s about the New Zealand whaling industry in the 1830s would hit Number One in the UK music charts. But it did! Wellerman sung by Nathan Evans and remixed by 220Kid and Billen Ted peaked at number one in the UK Official Singles Chart and after eleven weeks in the Top 100 still sits at number three. This amazing success has created a resurgence in interest in shanties and sea songs in general. Perhaps ironically Wellerman is not actually a shanty, although it is clearly a sea song. Unlike many sea songs that depict the harsh realities of life at sea its verses describe a fanciful battle between a whale and pursuing whalers while the chorus expresses the sailors’ hope of a resupply vessel arriving soon and bringing the luxuries of “sugar and tea and rum”.

The Origins of Sea Shanties

The origin of shanties is unclear – it has been said there are as many theories as there are sails on a full rigged ship – but the most likely is that they came from the worksongs of slaves working as stevedores on the east coast of the US, particularly the cotton ports. Loading cargo onto ships was not the only arduous job here; just as one of the jobs in an Australian shearing shed was pressing the wool, cotton was screwed before it was loaded onto a ship for export. In both cases the light fluffy fibre was compressed to get more weight into a ship’s hold. Pressing wool was no fun, but in the humidity of Florida screwing cotton was probably worse. It is generally assumed that the stevedores’ worksongs derived from farm labourers’ songs and thence from some earlier tradition in Africa.

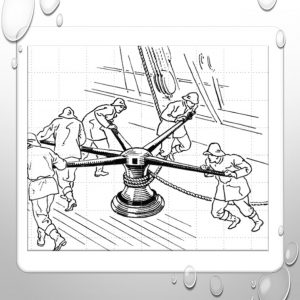

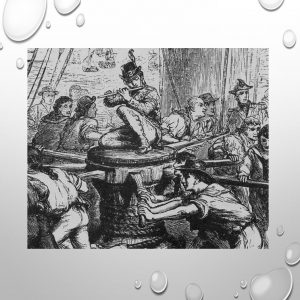

Shanties, as work songs aboard ship, arose from these previous traditions in the early 1800s with the advent of “packet” ships. These were mixed cargo and passenger vessels which kept, or at least tried to, to a regular schedule unlike previous ships that sailed once their holds were full of cargo. The owners of these vessels did what all good capitalists do to maximise their profits – they reduced the crews and worked the men harder. While it was the wind that drove the boats it was human muscle that did everything else. Sails and yards needed to be hoisted up masts, anchors needed to be weighed, and sails needed to be trimmed – all by manual labour. It was to maximise the output of the crew that shanties came into use. The shanty set the pace and synchronised the effort, with the strong beats in the song indicating when the men should haul on the rope. It was said that a good shantyman was worth an extra four sailors.

A shanty for every job

There were four main tasks, and each has characteristic shanties. The long haul shanty was used when a job was expected to take a long time, such as hauling a sail or a yard up a mast. A long haul required endurance rather than outright strength. These shanties were more melodic and often told more of a story. A good shantyman would improvise by drawing verses from other shanties or making up his own to stretch out the shanty until the task was completed. By comparison a short haul shanty was for a job which may require greater force, but which would be completed relatively quickly. This was typically used for hauling sheets or braces to adjust the sail setting. These shanties have much more energy and stress on the action words.

The capstan was used primarily for weighing or raising the anchor, but could also be used for hoisting yards and sails – particularly the heavier mainsail. Weighing anchor was a task that could take up to an hour. British Admiralty standards were that the anchor rope and chain should be eight times the depth at high water so there was a lot of rope to haul in. The anchor was – hopefully – fixed to the seabed and the rope would be covered in mud and debris from the harbour floor so when the anchor rope was hauled in it was the boat that moved, not the anchor. Capstan shanties are characterised by a steady beat – somewhat like a march – and without any strong beats.

It is a fact of life that wooden boats leak; a poorly maintained boat might leak a lot! Water that leaked in had to be pumped out – hence the pump shanty. These are similar to capstan shanties, but tend to be faster with the tempo being set by the style of pump. The older type of pump was driven by handles moved up and down much like a railway hand car, later flywheels turned by hand and a crankshaft were used which had a much smoother action.

There is another set of shanties that are more ceremonial and were not used as work songs. These were for special events like leaving or arriving at a port or crossing the equator. Perhaps the best known of these is the Dead Horse Shanty. When sailors signed on to a ship they were given a month’s advance – intended for them to kit themselves out, but more often spent at the dockside pub. The first month at sea then was spent repaying this debt and it was only after this the sailors began to earn money for themselves. An effigy of a horse would be made and thrown overboard, and the Dead Horse Shanty would be sung.

Shanties are also about history.

Shanties are not just about singing, they are also about history. Shanties trace not only the work that sailors did and their leisure time with women and grog in distant ports but also general history and its heroes like Admiral Nelson and Admiral Benbow, famous sea and land battles. Ships’ crews were multinational and each nationality brought their own shanties and lingos to the ships. As long as a sailor could do his job he was accepted. Sailing ships was hard work, often in appalling conditions, and few ocean-going sailors lasted beyond their fortieth birthday!

There is a generous supply of sea songs which are not shanties – of which Wellerman is one. These are the songs sailors sang for recreation while they were off watch, and perhaps which old sailors sang in their local pub. These songs, sometimes called forebitters, are more likely to be melodic and have multiple line verses and choruses. Whaling has produced a lot of songs, including at least two relatively (twentieth century) recent songs about whaling in our neck of the woods Queensland Whalers and Ballina Whalers, both written by Harry Robertson. The doings of the Royal Navy also offer plenty of material. We forget what an unsung hero actually means, but Admiral Benbow is not unsung and will perhaps be remembered forever.

Start Singing with Shanty Brisbane

If this has fired your interest in shanties you might come down to Southbank where Shanty Brisbane meets and sings twice a month.

Details are posted on the web (https://riderswithpace.wixsite.com/shanty-brisbane) and on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/shanty.brisbane). We sing sea songs and shanties for our own enjoyment and generally without instruments. Since shanties are generally quite simple most people can pick up the words and tune within the first few verses.

Our sessions are very informal; anyone who wants to lead can just start off a shanty whenever there is a gap between songs. We have all levels of expertise from singers who have been singing for decades to newcomers who have just stumbled upon us and are new to shanties. Others just come to listen. There are lots of sites about shanties on the web.

One of the latest (http://dave-wheatley.epizy.com/Songbook/) has words to many shanties and also provides YouTube versions by well known singers. Well worth a look.

Next session: 23 April at 7pm at Barbossa Bar at Southbank.

Feature image of some of the Shanty Brisbane singers by Jan Bowman – left to right, Maria Plumb. Rod Thompson, John Stafford, John Rayner, Malcolm Avery, Rod Stock, Sam Chittenden.

To the Shanty Johns , A fine and informative article indeed. Well Done ..Malcolm Avery