A while back I wrote this popular article about how:

- building approvals and planning approvals are different, and

- builders and developers are different.

I have now released a new Explainer paper covering the same topic with more clarity and depth. Below is a brief summary.

Builders are not property owners or developers

Some economists confuse builders and property developers (property owners), saying things like the following.

Suppose a home builder was keen to help supply new “missing-middle” housing…

…our prospective home builder would study the council’s Local Environment Plan (LEP), a document that is required by state legislation and is typically around 150 pages.

Builders generally do not consult planning regulations. Builders build homes designed by property owners or their consultants (though sometimes building companies also act as a developer).

This is extremely important. As I explain in the paper.

How much new housing is built is not a choice made by builders but by property owners. This is why the idea of property as a monopoly makes so much sense. Non-property owners can’t compete using non-property inputs. They must always buy property from a current owner to get into the housing game, and these current owners have no incentive to minimise the price they receive by rapidly increasing their sales or rapidly building new homes.

Planning and building approvals are different

Another common confusion is that building approvals, which are reported regularly by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) are caused by the planning system.

But planning approvals and building approvals are different.

A planning approval is the first step in a development process and a building approval is the last step prior to construction. A planning approval is needed to asses a project against planning regulations, and a building approval assesses a building against the building codes.

Because there are risks in property, usually between planning and building approvals property owners will pre-sell. Because of this, the market regulates how quickly planning approvals are converted into dwellings. When the market is booming, many approved projects are pushed through to construction. When the market is soft, approved projects are delayed, increasing the buffer stock of projects with planning approval.

Buffer stocks

Market risks, variations, and lags mean that it is sensible for property owners to keep a buffer stock of planning approvals. They can then respond quickly to new market conditions by selling and starting construction, by delaying without major capital commitments, or by varying the approval and seeking a new one for a different project that meets new market preferences.

But they don’t need to keep a buffer stock of building approvals because these are quick and come after the sales have verified the project is viable.

The below diagram helps show the choices in the process. Property owners choose to apply for a planning approval, which generates a stock of applications being assessed. Out of this stock, the planning agency will approve projects, and those become a buffer stock of approved but undeveloped dwellings in the system.

The flows out of this approved buffer stock are regulated by market conditions. For the economists out there, the equilibrium is in the flow rate of new homes, and the stock of constructed homes can only change via this flow. The decision – the ultimate choice to turn on a supply tap – comes from property owners when they choose to construct out of the buffer stock of approved projects.

Like most things in economics, there is an optimal choice. Even when it is profitable to build, it can be more profitable not to build, because development-ready land rises in value over time, and over-supplying housing means selling at a discount.

The absorption rate equilibrium come from the balance of these considerations in order to maximise total returns to property ownership over time.

That there are large buffer stocks of approved projects suggests to me that the absorption rate is not being constrained by decisions about planning approvals by regulatory agencies.

A useful analogy is eating. Just because your fridge is full, doesn’t mean you eat everything as quickly as you can. You wait until your appetite – your demand – grows over time. Eating faster than this adds no value. Filling your fridge with a buffer stock doesn’t make it optimal to eat faster.

A recent article in The Age, for example, documented that:

there are active permits for almost 100 such sites that have not been acted on – 118 residential buildings and almost 22,000 apartments where work has not commenced. At least half of the permits are more than two years old.

It has also been intriguing to watch the misinformed pile-on targeting the Greens federal MP Max Chandler-Mather, such as in the below article, about his endeavours to influence local planning, which all confuse upstream planning processes with actual decisions about constructing new homes.

In this particular case, the project in question is my own “backyard” and I am intimately involved in local planning matters.

The hilarious part about the two towers in the photo is that the property owner of this site already got planning approval for five shorter towers in 2017! They have delayed the project to take advantage of the flexibility available to them to resubmit new applications until they are satisfied the market demand is there.

In fact, within a couple of hundred metres of this site are thousands of approved and undeveloped apartment projects.

Just last weekend I spoke to a Brisbane developer who said that six of their planning-approved projects are on indefinite hold because of market conditions, both in the apartment buyer market and the construction market. These approved projects are their buffer stock. They are still adding to that buffer stock, acquiring sites and pushing designs through the planning system, but adding to that buffer stock won’t accelerate new development.

How big are these buffers?

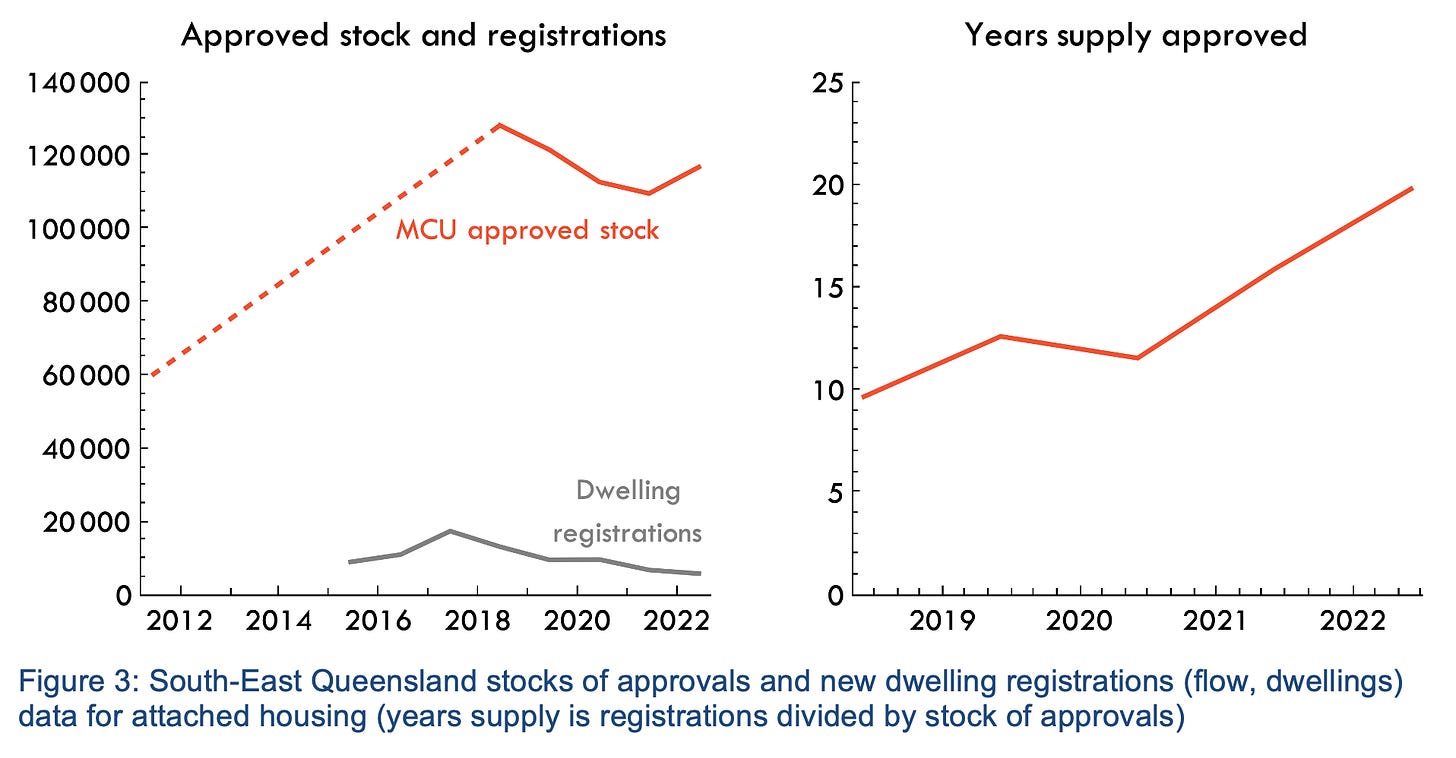

In my new Explainer paper, I show the size of these buffer stocks in the Queensland planning system data. In terms of how many years it would take to exhaust this buffer stock at current rates of new construction, we are talking 5 to 6 years for detached housing lots.

For apartments, these projects are generally riskier, so a larger buffer stock is maintained across the market, with about 20 years of flows already approved.

Notice that both of these buffer stocks have grown substantially in recent years.

If we want to have a sensible discussion about planning and housing markets we must first be very clear about the decisions and processes involved. Too often, property owners and builders are conflated, and too often we ignore the simple fact that planning regulates where homes are built, but not how quickly they are built. Property owners are the only ones who can choose to build new homes, and they sensibly maintain a buffer stock of approved projects so they can optimally respond to changing market conditions.

Republished with kind permission of the author – see the original article here – https://www.fresheconomicthinking.com/p/explainer-building-and-planning-approvals?sd=pf