The 1980s was a decade of change and energy, heralded by Bob Hawke’s rise to power in 1983, and a gut feeling that things were on the move. They were. Hawke’s Government moved to the middle ground and won four terms, followed by Paul Keating’s (1991–1996) moves to write a ‘new national story’, including where Australia really was in the world.

For me, the decade from the mid-1980s to the mid-’90s was punctuated by an increasing interest in our region. For my peers, South-East and East Asia had been desirable destinations for at least the ten years previous, and by the late ’70s several artists had developed links with their Asian counterparts. In the ’80s it was ANZART (joint Australia-New Zealand projects) and the ARX (Artists Regional Exchange) series of events that led the way, developing connections with artists and organizations that remain alive today. By the late 1980s and into the 1990s, the Australia Council was creating new links through artist residencies at Asian art schools, and Melbourne-based Asialink — established to develop broad cultural links — had begun to tour art and craft exhibitions and, with support from the Australia Council and the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), took on the artist residencies as part of an ‘Australian Art to Asia’ package. At Asialink, Alison Carroll and at DFAT, Neil Manton, both led with passion and determination. At the same time the Australia Council, under Max Burke’s leadership — with the remarkable Carillo Gantner as a member of Council — began supporting a dramatically increased number of projects in the region (much to the chagrin of a few art Europhiles).

In the craft and design world, connections with Asia date to the 1960s with links between Australian and Japanese potters. Around this time Japanese and East Asian ceramics were being acquired for most state gallery collections. (It’s worth noting that the World Crafts Council held its 8th Congress in Kyoto in 1978, followed by a conference in Jakarta in 1985.) Robert Bell’s 1989 International Crafts Triennial in Perth was memorable for its dynamic mix of American figurative ceramics, European metal and Australian craft, highlighted by amazing Japanese sculptural fibre.

These ideas and events were wrapped into the landmark first Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT1) at the Queensland Art Gallery in 1993, fervently led by Doug Hall with Caroline Turner and crucially, with the direct support of people within the Queensland Government, particularly Premier Wayne Goss. The strategic appointment of Richard Austin as Chair of QAG Trustees (in 1987) had signalled this shift in direction. It was a perfect storm. The first APT exhibition of predominantly installation-based art was raw, empowering, ideally timed and gathered a devoted national and international audience. My lingering memories are of Montien Boonma’s inspired stack of multiple terracotta bells and Dadang Christanto’s memorial for victims of injustice, plus a host of new and familiar visitors and lively discussions.

By the latter I refer to the APT1 symposium which, by its intense exchanges of emphatic voices — from colleagues from Asian countries, the USA and Australia — a kind of schism appeared which led to a change in our thinking and curatorial stance. By degrees at first, but forever. We were now being given permission to think for ourselves and regionally, and to shift a fix on long-held Euro-North American perspectives. It’s not an extravagance to claim that this revision, given succour in Brisbane, permeated nationally. The time was ripe for this too.

The second and third APTs, no less lively than the first, followed in 1996 and by 1999 — largely due to the impetus and general interest in the APTs — plans were underway for the construction of a substantial contemporary gallery to house such major events. Goss was a base-line supporter of the new gallery championed from the beginning by arts minister Matt Foley, and subsequently backed by Premier Peter Beattie. As part of the Queensland Art Gallery, the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) opened to national fanfare on 1 December 2006, with APT5 as the main event.

Since then there’ve been five more APTs, one every three years including the latest, APT10, opening 4 December 2021. Over almost three decades the Triennials have come into our lives with varying themes, scores of artists from an increasingly broad range of countries and regions, a wide range of media and occurring in differing political times. A considerable number of curators and producers have been involved both within the Gallery and without, although, since 1999, as expertise developed, mostly within.

The APTs have also given us a wealth of specifically commissioned artworks with much of these becoming part of the QAG’s dynamic Asia-Pacific collection.

Pacific-rim connections and projects have grown concurrently, and continue to develop strongly — witness the substantial representation from NZ and Pacific islands since the 5th and in the current APT — but that’s another history (I’ll not cover here). However, it needs to be said that the inclusion of artists from the Pacific certainly broadened the range of media in APTs by encompassing traditional arts and craftwork, notably fibre, textiles and weaving.

As the triennials progressed it seemed as though their territory was ever expanding and, starting with APT6, began to include artists from (the strangely named) West Asia and (the equally tricky) Middle East including Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Turkey, Armenia, Lebanon — well beyond what could comfortably be called ‘our’ region; a kind of curatorial and political cherry-picking I thought at the time — but with this year’s triennial the spread of artists is more controlled and agreeable.

APT10

Despite the gravity of our times, APT10 is grand and diverse, forbidding even at first glance but, taken a section at a time, richly rewarding. Like similar recurrent exhibitions it’s a mixed bag but anyone who’s interested in contemporary art will find things to love and be moved by. Strolling the three levels of GOMA’s big galleries and smaller spaces, I found myself initially drawn to artworks that were more intimate rather than the more obvious; a simplistic approach to a curatorially complex show. These included art by three artists whose work (found in different parts of GOMA) was of a similar scale and eloquence.

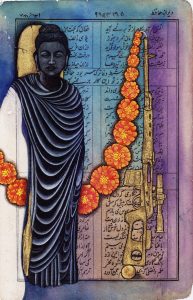

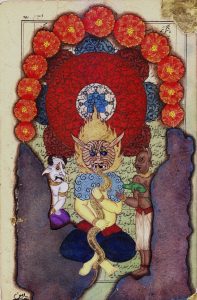

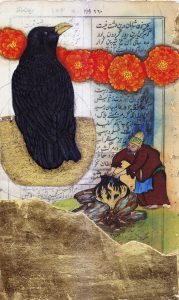

Amin Taasha (who lives in Yogyakarta but comes from the Hazara community of central Afghanistan near the Buddhas of Bamiyan) uses sheets of poetry — from a book by fourteenth-century Persian poet Hafiz — as the base for a major painting project. Onto these pages he renders in watercolour and gold leaf, figures and motifs from his own life and the mythology of Afghanistan.

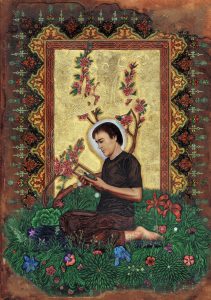

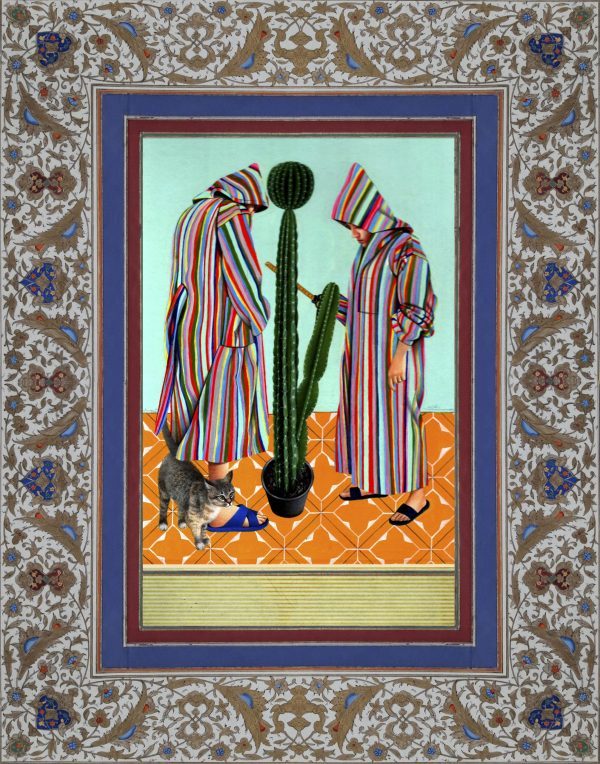

Also referencing Persian poetry is Maryam Ayeen and Abbas Shahsavar’s series of ten miniature paintings in gouache and watercolour — witty, moody self-portraits of the couple — illustrating private (mostly illicit) scenes taking place in their domestic space in Tehran.

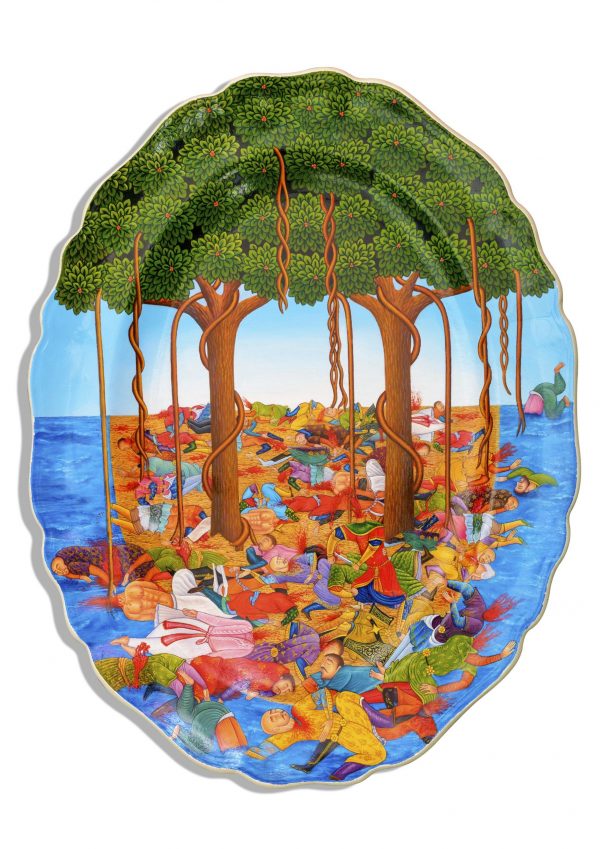

Adeela Suleman is represented in part by eight luxuriantly painted works on vintage ceramic plates; a balance of domestic objects and sheer painting skill with bloodied scenarios that resonate with contemporary conflicts. She uses techniques of South Asian miniature painting and draws from traditional images of violent historical encounters, including a mid-eighteenth-century painting from the MET in New York.

The most contemplative space at GOMA (for me on the day), was gallery 3.5. The mix here — featuring Lee Paje’s (The Philippines) two large-scale works of oil on copper; Nguyễn Thi Châu Giang’s (Vietnam) series of free-hanging silk paintings using ink and watercolour to depict female figures; Hoa Liang’s (China) suite of small, darkly subtle landscapes, also on silk; along with the aforementioned miniatures of Amin Taasha (Pakistan) — was charming and complementary.

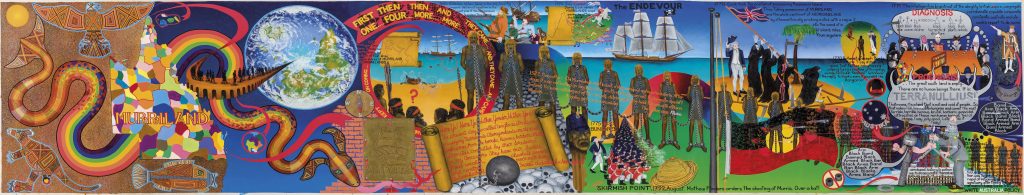

Just outside gallery 3.5, in the ‘Pavilion Walk’, and contemplative in another way, are Gordon Hookey’s (Waanyi people, Queensland) two ambitious oils on canvas and linen sharing the title, MURRILAND. With humour and verse Hookey boldly paints a panoramic narrative of an Australian history largely omitted from mainstream discourse.

In other spaces in GOMA you can find bright pandanus mats by a group of female Malaysian weavers from the Bajau Sama Dilaut community and discover diverse art from the Pacific including the ACAPA Pacifika Community Engagement Project, Air Canoe, Uramat Story Songs and impressive hand-built ceramics by Mary Gole from Papua New Guinea and three artists from Fiji.

I haven’t touched on the Yolngu/Macassan Project, various artist’s videos or the Cinémathèque program — and there’s still much more in this tenth edition of the triennial.

As QAG Director Chris Saines neatly put it in the APT10 catalogue intro, it’s a time ‘for both reflection and celebration. This milestone . . . has been reached through an unprecedented shared effort from participating artists and curators, writers, advisors and interlocutors from across the region’.

A strategic evolution over thirty-plus years. May the adventure continue.

The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art closes Anzac Day, Monday 25 April 2022.

Across both venues, GOMA and QAG, Brisbane.

We have one month left to see it all.

Cover image:

Maryam Ayeen and Abbas Shahsavar / Iran b. 1985 & 1983 / ‘Fall in dopamine’ (installation view) 2021-21 / Gouache and watercolour on paper / Courtesy: The artists Photograph: Merinda Campbell, QAGOMA