Vicious Lawless Association Disestablishment Act: A case study

It is 2015. Bob, Greg and Luong have been doing it tough. They have not been able to find work since the BP refinery at Bulwer Island in Pinkenba closed. On Wednesdays they hang around the public toilets in Boundary Street, West End and wait for the 4pm food handout. One day, Greg starts playing a tune on his harmonica while Bob claps along and Luong puts his hat down on the footpath so passers-by can throw them a coin or two.

Greg, Bob and Luong do not have a busking permit. They are charged with begging in a public place under section 8 of the Summary Offences Act 2005. This offence has been added to the list of ‘declared offences’ under the Vicious Lawless Association Disestablishment Act 2013 (‘VLAD’). Luong, Bob and Greg are charged under VLAD and are found guilty. The sentencing judge does not give them a prison sentence for the begging offence, but is forced to sentence them to an extra 15 years in prison.

Luong, Bob and Greg end up in the same prison as Barrie Watts and Brett Cowan. Watts is serving life imprisonment for his part in the abduction, rape and murder of 12-year old Sian Kingi at Noosa in 1987. Brett Cowan is serving life imprisonment for abducting and killing 13-year old Daniel Morecombe in 2003.

*

Why do we have criminal law? To punish bad behaviour? Encourage good behaviour?

Why do we put people in prison? To punish them? To rehabilitate them?

*******

Friday 27 September 2013 things get heated at the Gold Coast. The Gold Coast Bulletin reports that about 20 Bandido bikies, wearing their club colours, storm into the Aura restaurant at Broadbeach and ask a fellow bikie to come outside. Once outside, the bikies start fisticuffs. Later, reports surface that up to 50 Bandido bikies went to Southport police station to support arrested gang members. Three bikies sustain injuries requiring hospital treatment and four police officers are injured but don’t require hospitalisation. By the end of the day, 18 people have been charged with offences including public nuisance, assault, obstruct police, assault police, disorderly on licensed premises and an unconnected stealing matter.

Tuesday 1 October 2013, Premier Campbell Newman says to the Brisbane Times about the incidents at Broadbeach that the state could not afford to give second chances:

‘Every Queenslander was dismayed and angry by the scenes I saw on the Gold Coast on Friday night… They are criminals. They are thugs. They deal with drugs and prostitution, they use fear and intimidation to scare Queenslanders. They are not very nice people. They are criminal, motorcycle gangs.’

Tuesday 15 October 2013 Attorney-General Jarrod Bleijie introduces the Vicious Lawless Association Disestablishment (‘VLAD’) Billinto the Legislative Assembly. The Bill is declared urgent. Independent MP Peter Wellington objects because he has not been provided a copy of the Bill. The Attorney-General explains the urgency of the legislation, referring to the incident at Broadbeach and at the watch-house afterwards. The Legislative Assembly spends 52 minutes, from 1:55am to 2:47am, considering the provisions of VLAD in detail. The Legislative Assembly votes to pass VLAD in the early hours of the morning. On 17 October 2013, Governor Penelope Wensley, on behalf of the Queen, assents to VLAD and it commences that day.

VLAD uses the term ‘declared offence’. Declared offences range from murder to manslaughter and possessing more than 500 grams of cannabis. The list of declared offences can be expanded by a regulation, which will not be scrutinised by the Legislative Assembly until after it is made. Therefore, it is possible that offences such as busking without a permit will be added to the list.

VLAD imposes heavy additional sentences on vicious lawless associates who commit declared offences. This is the usual base sentence plus 15 years’ prison, to be spent wholly in prison. If a person is an office bearer of the association, he or she gets an extra 25 years in prison. No parole before this time is up. These sentences could be reduced if a vicious lawless associate cooperates with the police commissioner. Once in prison, people convicted under VLAD face solitary confinement and compulsory pink jumpsuits.

Under VLAD, a vicious lawless associate (‘VLA’), is a person:

who commits a declared offence, and

is a participant in a relevant association, and

committed the declared offence ‘for the purposes of, or in the course of participating in the affairs of, the relevant association’.

However, a person is not a VLA if he or she proves ‘that the relevant association is not an association that has as one of its purposes, the purpose of engaging in, or conspiring to engage in, declared offences’ (section 5(2)). Section 5(2) reverses the onus of proof and erodes the presumption of innocence. The presumption of innocence is recognised Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 11 and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights article 14(2):

‘Everyone charged with a criminal offence shall have the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law’.

The onus of proof and presumption of innocence have been recognised as fundamental to Australia’s system of criminal justice. As Justice Mary Gaudron of the High Court of Australia in Petty & Maiden v. R (1991) 173 CLR 95 pointed out:

‘it is for the prosecution to establish guilt beyond reasonable doubt… it is never for an accused person to prove his innocence.’

Her Honour quoted the 1935 English judgment of Woolmington v. DPP (1935) AC 462:

‘No matter what the charge or where the trial, the principle that the prosecution must prove the guilt of the prisoner is part of the common law of England and no attempt to whittle it down can be entertained.’

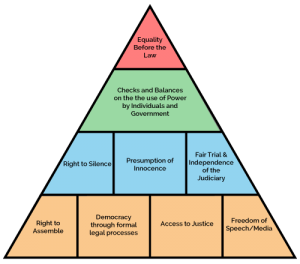

The presumption of innocence is part of something called the rule of law. The rule of law is a bit like the Triantiwontigongolope, in that it’s hard to define – it ‘isn’t quite a spider and isn’t quite a fly’. Unlike the Triantiwontigongolope, however, the rule of law is not a ‘little joke’. It is a cornerstone of civilised society under a parliamentary democracy. First year law students learn about it. Some promptly forget about it. Others become deeply impassioned about it. The rule of law is often shrouded in complexity but the following diagram from the Institute of the Rule of Law summarises it nicely:

The Rule of Law Institute has distilled the rule of law into ten principles which practically demonstrate its application. The three most relevant here are:

The Rule of Law Institute has distilled the rule of law into ten principles which practically demonstrate its application. The three most relevant here are:

- The separation of powers between the legislature, the executive and the judiciary.

- The law is capable of being known to everyone, so that everyone can comply.

- All people are presumed to be innocent until proven otherwise and are entitled to remain silent and are not required to incriminate themselves.

See the green bit in the pyramid and the first principle – ‘Separation of powers’? That bit is important. Effective democratic government relies on separation between the legislative, executive and judicial arms of government, as the Honourable Justice Margaret McMurdo, president of the Court of Appeal, explained on Friday 25 October 2013 at the Queensland Law Society’s Senior Counsellors’ Conference.

The separation of powers means that the Legislative Assembly legislates, the executive (Premier, Ministers and public service including the police) administer and enforce the law while the judiciary administers the Court system and sentences offenders. In the context of criminal law, we see the separation of powers in action when the legislature enacts the criminal law. The police on behalf of the executive investigate and prosecute alleged breaches. Defence lawyers, who are officers of the court, represent accused people. For serious crimes in the District and Supreme Courts, a jury decides whether or not the accused is guilty. If found guilty, the defendant is sentenced by a judge.

However, there is nothing entrenching the separation of powers in Queensland. VLAD strikes at the separation of powers. Instead of that hallowed separation between executive, legislature and judiciary, VLAD permits the executive to encroach onto the territory of the judiciary.

VLAD does this by imposing compulsory sentences for members of vicious lawless associates. This means that the legislature is doing what the judiciary would usually do. The judiciary is particularly well-placed to decide sentences. Most judges work as lawyers for years before appointment to the bench. Lawyers have a duty to the court, to the client and to the law. Sentencing judges are skilled at weighing factors such as the gravity of the crime, any remorse by the offender, comparable sentences for comparable crimes, antecedents of offender and cooperation with authorities. They are impartial and objective. They have the benefit of tenure. This means they can impose a sentence as they see fit without risking losing their job, although they don’t do it perfectly all the time.

VLAD means that a person will face an extra 15 or 25 years in prison on top of the base sentence. There is no room for the judge to deviate from this. This is why Luong, Bob and Greg ended up in prison for 15 years. The only possible reduction is if the offender cooperates with authorities.

In enacting this legislation, the Legislative Assembly has effectively decided to lock some people up and throw away the key. It appears to be based on a belief that there are some people that are beyond rehabilitation. Precisely who these people are is not made clear. This legislation is designed to target criminal motorcycle gangs. However its application is broad and vague.

Vagueness is the enemy of criminal law. The rule of law requires the law to be capable of being known to everyone, so that everyone can comply. VLAD’s definition of ‘vicious lawless associate’ is as clear as mud and the definition of ‘association’ includes

‘any group of 3 or more persons by whatever name called, whether associated formally or informally and whether the group is legal or illegal’.

This is why Luong, Bob and Greg, were captured by VLAD. This provision strikes at freedom of association. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, article 22, provides:

‘Everyone shall have the right to freedom of association with others, including the right to form and join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

No restrictions may be placed on the exercise of this right other than those which are prescribed by law and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public safety, public order (ordre public), the protection of public health or morals or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others…’

So the question becomes, are the restrictions VLAD places on the rights of citizens to meet with others and pursue a goal, necessary? We need to start debating these issues for longer than 52 minutes and form considered opinions about them.

*******

Why do we have criminal law? Why do we put people in prison?

Under VLAD, a person is given a lengthy additional prison sentence because of who they hang around with rather than because of acts they have done. VLAD does not operate as part of the criminal justice system in accordance with established principles of criminal justice.

In a parliamentary democracy in the Westminster tradition based on the rule of law, parliament is supreme. This is because it reflects the will of the people who elect its members. Ella Humphreys wrote for Overland on 6 February 2014:

‘What happens when the laws are patently unjust? Are judges expected to stay silent simply because parliament is “supreme”? Silence doesn’t seem the best option when the Liberal national party has a majority in legislative assembly, there is no upper house, and bills are rushed through without much consultation with legal or community groups.’

In Queensland in 2014, democracy and the criminal justice system are not made of great strong stones. They are fragile, like a tiny plant. They require tending by people with a conscience – people who care, people who are prepared to speak up when they see injustice. Speaking out now may prevent the story of Luong, Greg and Bob coming true.

© Marissa Ker 2014

Facts current as at 16 April 2013

Marissa Ker is a lawyer and writer. She has particular expertise in legislation and an interest in criminal law and the rule of law.

Thank you for writing this. While I agree something had to be done about the crimes being committed I firmly believe the premier went overboard and acted more like a dictator than an elected premier. I also believe the ‘out of control event’ legislation is ridiculous as well. I am in the process of organising a fundraiser and was appalled to discover I could be charged if something goes wrong even if I abided by all the rules and did all I could to make it a safe event. Ultimately no one has control over the actions of another so they should not have to bare the responsibility for them.

Good luck with your battle.

Well I guess Campbell Newman is to be congratulated for his respect for civil liberties. do you think he could extend that concern to the welfare of Heather Brown on the Queensland Downs.

Have a listen to the 23 minutes audio of the Alan Jones show broadcast last Thursday. I do not, ever, listen to Jones, but the audio of this show is going off in the social media, so I listened to it today…….. and it is sensational. The first 15 minutes are a summary of recent events in Q and then there is an interview with Heather Brown…….. most of the info about the events on the Downs I hadn’t heard about.

First I heard about the granting of part of the military land to Wagner last year.

Watch this saga unfold. Ian McFarlane might just have an Indi rerun on his hands.

http://www.2gb.com/article/alan-jones-heather-brown-0#.U23VLCh9Lpd

Sonia, you have made a good point about the extent to which we have control over the actions of others.

Excellent article! I am using it for my students as a case study for their final assignment.