How does Australia embrace its First Nations’ knowledge of life in the Australian environment? Through the two lenses of architecture and anthropology Paul Memmott has explored this question over his nearly 50 years of walking with and working for Aboriginal communities.

Sharing oysters and a beer at a Vulture Street café recently with a life-time friend Paul Memmott reminded me of when a group of us spent time with Paul on Gununa or Mornington Island (MI) in the Gulf of Carpentaria back in 1976.

Back then and freshly landed from taking the ‘hippie trail’ overland from London to Australia I got the chance to join a research team to work with Aboriginal Elders on the Island. Relying on Paul’s relationships with the MI community, that brief period of immersion within an Indigenous community was awe-filled for me, a window onto understandings I did not know I had to have.

Paul taught me about the meaning of ‘Country’ to Aboriginal people and what traditional ownership means in terms of rights and tensions. I didn’t know anything about the dictates of skin relationships, or laws governing hunting and ceremony. I learnt to pay the true price for Aboriginal art and that if something goes missing it’s not been stolen, just redistributed. And you cannot simply cut up a dugong, it has to be dissected and distributed according to custom.

Turtle eggs feel rubbery and dugong tastes like oyster-blade steak. Then if you eat food from the sea and food from the land in the one meal the lore says you will become very sick (malkri sickness).

I watched women dig wells deeper than the women were tall and how they read the movement of schools of fish way offshore. We cooked fish taken straight out of the sea and placed on the fire, no scaling or gutting needed and no utensils. I heard violent exchanges after the closing of the wet canteen and saw that jails don’t need doors when you live on an island. I saw the failure of government-supplied housing, the crippling price of groceries and flights into remote communities, one family’s welcoming of electricity supply to their tin hut and an infestation with feral cats that seemed to be ignored.

There was a lot of love, laughter and ceremony overlain on the hardship of settlement life. I now realise the extent of my ignorance then of black history and in particular Mornington Island’s history of colonisation and of strong community struggle for their rights and self-determination

The beginning of the Aboriginal Environments Research Centre and its Archive…..Paul at the men’s dance ground, Mornington Island, 1974.

Big seeds Paul has sown

The project I was involved in back in 1976 was an early one in Paul’s work story. Since then he has spent the 5 decades in close connection with Aboriginal communities across Australia including many in North Queensland.

Paul is another of our local West End legends.

Paul with Brisbane elders Uncle Bob Anderson and Uncle Des Sandy at Kuril Dhagun, the dedicated cultural space at the State Library, 2016.

He’s reserved and modest about the things he has done and the big seeds he has sown to drive change on a number of fronts. He would say he didn’t do them alone. In every community and every engagement Paul has had Indigenous mentors, he has been there to learn. He has taken those decades of learning into new contexts to challenge, to advocate and to promote different ways of thinking and problem-solving.

The big areas where Paul has sought knowledge and driven change over these decades include:

- Communities have shared their knowledge with him, knowledge evolved in, for and about the Australian landscape by its First Nations’ people over thousands of years. Through his respect for this knowledge he has become a collector and curator of it, archiving it and deep-diving into the whole question of Aboriginal shelter, their ethno-architecture, and what it tells us about culture and Aboriginal society;

- His concern for Indigenous rights combined with his understanding of Aboriginal culture has led him into working across Australia on land rights disputes and native title claims – as a researcher and expert witness – and on core community issues such as homelessness, family violence, culturally sensitive services, organisational governance – as a trusted advocate,

- One mission has been the reform of architecture studies specifically Aboriginal Architecture and how it could drive a more authentic Australian design. He has worked on several fronts to further this question – on architectural education and how it equips its students, and on ways to improve Aboriginal participation and leadership in the architecture profession.

Breaking barriers

First and foremost, Paul’s focus is on architecture but not the architecture of Grand Designs. Rather, he has a deep sense of loyalty to ‘shelter’ as a fundamental expression of human culture and history and the basis of well-being. The thinking that interested him was more about architecture without architects, the architecture people build themselves and what it reveals about culture. Paul would never have embarked on the Grand Designs path of architecture. His parents were two of Australia’s leading pottery artists – Harry and Cootch Memmott – a tradition handed down through Paul’s hardworking Scottish ancestry. Instead of pursuing the potter’s way, Paul became an architecture student at UQ in the mid-60s, when it was a hotbed of radicalism with its anti-Vietnam war protests, women’s and black rights struggles, and emerging environmentalism. In the Architecture School at that time the focus turned to exploring new frontiers.

In 1968 Paul’s year group had a project to design and actually build dwellings for the future on the land adjoining the University Lake. They then had to live in them for a week. This ‘experimental learning’ is hard to imagine now.

Students out of this architecture degree wanted to have an impact. One ‘squatted’ in the derelict rowhouses on Park Road / Coronation Drive. His renovation of one of them led to their protection and rehabilitation; and to the restoration of the Petrie Terrace rowhouses. Others moved into run-down houses in Fortescue Street in Spring Hill or Cambridge Street in Red Hill. These ‘Queenslanders’ were saved and renovated and are still there today, facing down the demolition industry that has wiped out so much of inner Brisbane.

Other students helped organise the Aquarius Festival at Nimbin in ’73 or helped Oogeroo Noonuccal construct community buildings on Minjerribah. Another went from Black Rights campaigning on campus to starting up the Workers Health Centre for the union movement.

That era of architecture produced many pathfinders.

The trigger: failed housing in Aboriginal communities

Public housing provision was the ‘solution’ governments delivered to fix the Aboriginal ‘housing problem’ and it has been a big failing for Aboriginal communities. In 1972 as a final year architecture student Paul put his hand up to evaluate two housing projects proposed for Mt Isa and Cloncurry.

In Mt Isa he was struck by the complex socio-spatial arrangement of the Aboriginal community camps on the town fringes. He was hooked. This analysis of Indigenous design led to his work on the spatial behaviour of Aboriginal people in North-west Queensland. Paul extended his knowledge further when he added social anthropology to his architecture degree in 1974-5, completing his PhD in 1979 at the University of Queensland (UQ).

Paul’s curiosity about the highly organised community living of these settlements was the springboard for his life’s work on Aboriginal (ethno-) architecture. He has been firing up architecture and the education of the architectural profession ever since.

Paul Memmott with the Brown family, chatting in their outdoor living room, at Weilmoringle pastoral settlement, northern New South Wales, 1978.

A cross-cultural man

Paul’s connection to culture is profound. He belongs to three skin groups across northern and central Australia. He has been initiated into different levels of ceremony, learning the relevant bodies of associated knowledge, rules and duties. He cannot talk to white people or the uninitiated about such Aboriginal business. Such is the regard for his cultural integrity and knowledge he was recently sought out by an all-Aboriginal organisation in Central Australia to undertake a cultural audit of their operations and service environment. The work was to ensure it was safely culturally grounded in the delivery of its services and work with them to develop improved capacity.

Building the knowledge bank: Mornington Island

Throughout his long association with Mornington Island Paul and his various teams have collected years of Indigenous community interviews, thousands of photographs and many other materials documenting island cultural life. The Aboriginal Environments Research Centre (AERC) [1] is a living archive, one of the largest stores of Aboriginal culture study in Australia, and it maintains strong connections to the community

Elders have passed on, the language may not be spoken by many any longer but the archive holds a rich store of that knowledge.[1] The paradox is that as the power, relevance and significance of Aboriginal knowledge is dawning on non-Aboriginal society, all are at risk of losing the thread of connection. Fifty years of accumulated research cannot substitute for the knowledge lost through colonisation and dispossession. The archive and the AERC hold that value for future inquiry.

Paul’s work interviewing elders to map the story places, the traditional geographic knowledge, on Mornington Island revealed that there is important place names and cultural associations every 300-500 metres. This insight about the ‘density’ of significant places has been recently applied to mapping of Brisbane River and West End story places. It is a way to help recovery from the early colonial record and maintain traditional owner knowledge of Yaggera country

Advocate and consultant

With his anthropologist hat on, Paul moved from housing into broader community concerns. Since the 1970s his professional life has run in parallel with key policy legislative reforms attempting to redress injustices and destruction of Aboriginal rights. Land claims were a big part of Paul’s work in the 1980s and 90s and then with the arrival of the Native Title era 1992-2010, he spent years working on Native Title claims across Australia

Paul’s work on Native Title on Minjerribah and Moreton Bay meant developing a full genealogy for every family of Quandamooka people (~2500 people) and mapping ‘Country’ from first contact to 2000. The result of this effort by the community, the legal team and Paul is that Title claimants now have the responsibility for co-management of the island in the future under the Indigenous Land Use Agreements signed with the Queensland Government.

Consultancy work expanded to include analysis of Indigenous social problems – family violence, disease, deaths in custody, health and welfare and homelessness. He was searching for good practice as to how Indigenous groups were addressing these. He did the first national overview study into family violence and he conducted the first survey of homelessness in Sydney and Darwin. The list goes on.

Campsites, spinifex and rainforest houses

Decades of cultural and architectural studies across Australia saw Paul produce his master work Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley in 2007. This big coffee-table publication describes and classifies the complex array of shelters, structures and settlements of Aboriginal society across the continent.

He is a taxonomist of the architecture by our First Nations. The work is ongoing, it has to be. It is all about the missing piece in our understanding of what Australian architecture is. At its core is the cultural significance of the socio-spatial dimension and through that, the observance of connection to Country. Country is everything, building on country makes architecture a verb, not a noun, a process not an object.

While Paul acknowledges some instances of pushback from mainstream architecture he seems pleased when he tells me that Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley will soon be in its second edition. His article on the whole topic of Australia’s ethno-architecture is the lead chapter in The Encyclopaedia of Australian Architecture (2011)[1] and he has prepared a volume on the Oceania-Australasian region’s architecture (200 entries) for the Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture of the World.

Paul’s determination to see Aboriginal Architecture acknowledged as an area of academic scholarship is hitting the mark.

Reframing architecture

For Paul the question becomes how can cultural knowledge be applied to improve service delivery to Aboriginal communities? The alternative is the failing service provision we see rolled out across the country without any, or the right, cultural groundedness. We see hospitals designed with their backs to the sacred river, birthing centres that are not appropriate for women’s business, jails and courthouses not aligned with cultural knowledge and grocery stores that don’t offer separation of people who for skin or marriage reasons are forbidden to interact.

And token efforts are everywhere – dressing up ordinary architecture with an ‘Indigenous’ flair or façade.

As an educator Paul has a sizable alumni of Indigenous and non-Indigenous graduates, many as PhD scholars and many of whom have moved on to directing their own architecture companies, or moved into government or industry employment.

He has championed ‘Aboriginal environments studies’ into the curriculum of under-graduate and post-graduate Architecture. His view is that as a knowledge area, ethno-architecture is now well defined and the curriculum needs to respond accordingly.

There is a new level of ‘receptivity’ to these innovations, something that Paul can appreciate after many years of chipping away. Just recently Paul assisted with a reform to the registration of architects so that it now requires completion of skills and knowledge acquisition about Aboriginal concepts of Country and appropriate ways of engaging with communities on architectural and urban design projects[1].

A current big goal is increasing the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island teachers in Architecture schools. For the substantive change that Aboriginal Architecture represents to our way of thinking about design in Australia it is vital that Indigenous architects head up the processes and / or teach the students and young professionals how to engage in co-design with Indigenous people at every stage.

His students are building the Indigenous architecture base, doing research into traditional ways, the causes of current social issues and community-centred ways of designing.

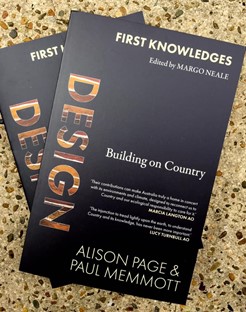

His latest publication is one book in a six-part series on First Knowledges. Design: Building on Country is a collaboration between Paul and Alison Page, a Walbanga and Wadi Wadi woman and design expert[2]. It is an engaging handbook about the material and spiritual makeup of Aboriginal design.

Functional sophistication, the high level of ingenuity across material and cultural elements, Environmental sustainability, connecting us to Country and responsive to climate and materials Storytelling, making the vital links to Country, ceremonies, totems and custodial duties. The challenge is to translate these principles into a response to our ecological crisis.

Recent publication launched this year at Avid Reader with Alison Page in the First Knowledges Series 2021

The whole idea of building on Country is a two-way challenge – to build a truly Australian design framework by incorporating and reflecting traditional ethno-architecture and to work, through co-design with Aboriginal communities, to bridge the yawning gap between impoverished badly-housed and poorly-serviced communities and the rest of Australia.

Out of a native title project for Main Roads in 2007 Paul has built a long-running skills, identity and well-being program for Aboriginal trainees. The last 14 years of the Workshops, held every four months, have attracted candidates from across Queensland.

At the commencement of the workshops, (Indigenous leader) Colin Saltmere explains that ‘the old people’ taught Paul a large amount of traditional knowledge in the course of his anthropological work in the 1970s, 80s and 90s, and as they have all passed away, it is Paul’s responsibility to now share and teach this knowledge back to younger Indigenous people. Paul then explains something of his early teachers from the Lardil, Kaiadilt, Kalkadoon, Yanyuwa, Alyawarr, Warumungu, Warlpiri, Arrernte, Dyirbal and other First Nations. Excerpt from the Myuma Group’s Aboriginal Identity and Well-being Workshops

Paul’s group of trainees from the Myuma Workshop in October 2021 – Paul led them into the cave sacred site after showing them how to address the spirit at the site, in this case Wiliyan-nguru, a Lizard Dreaming.

50 years of chipping away

Paul has had his share of awards, achievements and breakthroughs over the 50 years – in grants and qualifications, in the recognition awarded to his graduating students, and through his body of research reports. He is an accomplished professor with over 300 published papers and 100 technical reports.

This year he was awarded an Order of Australia medal (AO) for the part he has played in establishing ‘ethno-architecture’ as a field of endeavour and a masthead for Australian architecture. It was also in recognition of his contributions to anthropology, tertiary education and Aboriginal housing.

It has been a reciprocal arrangement – Paul has been given to by Aboriginal communities and he has given back. He has set his mind on collecting knowledge and seeding its usage by both Indigenous and white practitioners of mainstream architecture in collaboration. He sees the application of Indigenous knowledge to improving service delivery to Indigenous communities as a high priority reform.

Paul, through the AERC at UQ, has a number of local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Elders and scholars whom he engages as consultants into various environmental design projects in Brisbane. The most recent is the design guidance on the landscaping of the four new railway stations servicing the Cross-River Rail project, which each incorporate a set of Indigenous place references.

For the Rail project his group has a vision that they would like to have implemented by the time of the Olympic Games: all railway stations in SEQ to have a unique QR code that would enable the train traveller (including Games visitors and attendees) to link via an app to interesting cultural and historical information on the local Aboriginal places. These would be based on the ethnographic record for the city and its Indigenous knowledge bank.

References

[1] AERC https://architecture.uq.edu.au/research/aboriginal-environments-research-centre

[2] One on-going challenge lies in funding the technology transfer and reformatting needed to keep the paper and tape materials accessible. There can be no doubt that the invaluable nature of this material will increase with time.

[3] Philip Goad and Julie Willis (eds), The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture, Cambridge University Press, 2011

[4] The Australian Institute of Architects hosts a First Nations Advisory Working Group and Cultural Reference Panel, with a mandate to improve First Nations representation and engagement in the industry. Paul is the Group’s co-chair. https://thefifthestate.com.au/innovation/architecture/Indigenous-voices-giving-rise-to-better-architecture/

[5] Alison Page, Alison & Paul Memmott, (2021) Design: Building on Country, Thomson & Hudson, Australia

Congratulations, Mary, on this eye-mind-heart-opening piece of writing. Prof Memmott should be a household name for his life work that is an exemplary model of how colonisers past and present might learn, incorporate and benefit from our First Nations peoples and their knowledge. I’ll be sharing your article far and wide. I’d love all Australians to know this story and what we can all take from it into our own lives and work.