Do you remember the song Treaty by Yothu Yindi?

It was released in 1991 when Sallyanne Atkinson was the Mayor of Brisbane City Council, Wayne Goss was the Queensland Premier, and Bob Hawke was the Prime Minister.

It was the same year the Federal Minister Robert Ticker proposed that a Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation be established, and the Royal Commission into Deaths in Aboriginal Deaths in Custody was released.

Treaty

When released, Treaty was the first pop-song written by an Aboriginal group to chart in Australia.

It was written in response to Bob Hawkes’ failure to deliver the Treaty he promised three years earlier at Barunga, on Jawoyn country, east of Katherine in 1988. Hand crafted and written on paperbark; the statement was a document that amongst other things asked:

…the Commonwealth Parliament to negotiate a Treaty recognising prior ownership, continued occupation and sovereignty, affirming Indigenous people’s human rights and freedom.

The song Treaty contains the lyrics “Promises can disappear just like writing in the sand”. Hawke’s commitment to deliver his promise quickly dissipated as it was met with opposition from hard-right politicians, opposition leader John Howard, and members of his own party.

Hawke’s failings on Treaty had less to do with his rhetoric or “good intentions” – for historical documents demonstrate that he genuinely supported the idea of a Treaty. In the years that followed he expressed his regret at not being able to deliver his promise to enact a Treaty by the end of his government’s term.

30 years on, we are still talking about a Treaty.

My fear is that in a further 30 years, in 2051, we’ll be left in the same position saying: “Well I heard it on Twitter, and I saw it on Facebook. Back in 2021. All those talking politicians”.

Three decades have passed and we continue to talk. We talk of a Treaty at the national level, there is talk of Treaty in Victoria, WA, the Northern Territory and in Queensland.

Last year we had consultations which considered the Tracks to Treaty document. The Queensland Government agreed to the Tracks to Treaty Statement of Commitment, a declaration of joint commitment between Government and Indigenous relationships. State treaties are seeking to advance reconciliation and improve outcomes for Indigenous peoples at a state level, in response to local and regional concerns. Their focus and powers however are limited to state jurisdictions, meaning that federal responses and commitments are also needed.

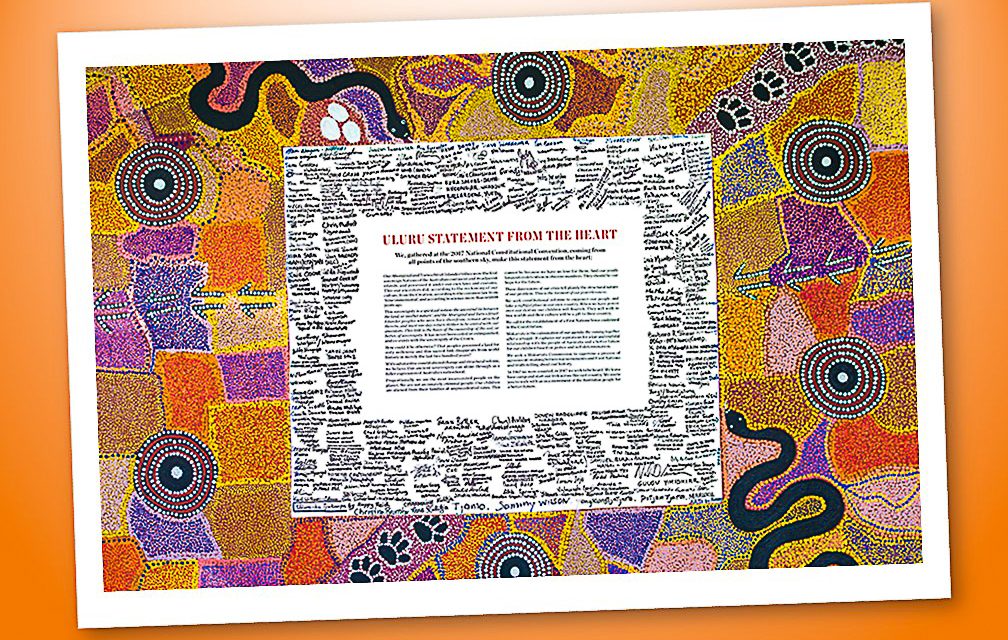

Uluru Statement from the Heart

We talk of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. The Uluru Statement arose out of the discussions of some 250 Indigenous delegates who attended the First Nations National Constitutional Convention in 2017. The Statement is a poetic, yet poignant declaration for constitutional reform. It is the culmination of community consultations and 13 regional dialogues which was run by the Referendum Council. While rigorous and robust debate occurred, the delegates agreed on three milestones for reform: Voice, Treaty and Truth – In that order.

We need to remember that the order – as it was developed through hours and days of deliberation and cultural authority – is a process that is thoughtful, deliberate, and in an order of what would work, can work, and will ensure we achieve change.

The Statement calls for a “First Nations Voice” to be enshrined in the constitution to secure Indigenous peoples’ involvement in political decisions. This would require parliament to legislate a representative body to constitutionally guarantee an Indigenous Voice. Constitutional protection is vital, for as the song reminds us, not only promises but voices can and historically have disappeared just like writing in the sand.

There has been much talk, misinformation, and fear mongering about how such a Voice would operate. Public, political, and media discourses have played a role in hijacking conversations equating an Indigenous Voice to Parliament to the establishment of a new “third chamber”, with executive and legislative powers. In actual fact, the proposed Voice never sought voting or veto powers, but rather seeks to operate as an advisory body whose representatives would inform and contribute to discussions as means to develop effective and culturally appropriate policy. The Voice would sit alongside Parliament but be free of any political allegiances.

It is more than disappointing that after a decade of consultative work, eight government reports and inquiries, and countless publications and commentaries, the Uluru Statement continues to be played down, dismissed, and framed as needing more “talk”. It must be remembered that the community consultations conducted by the Referendum Council were done so at the request and funding of government who explicitly sought insights into what constitutional recognition means for Indigenous peoples.

The second milestone that arose out of the community and regional dialogues, pertains to Treaty. Historically – such as at Barunga in 1988, or the Yirrkala Bark Petitions before it in 1963 – treaties are often seen as the driving force for change for Indigenous peoples. Yet, treaties are dependent on nuanced negotiations, legal challenges, and numerous other obstacles that can make it extremely difficult to achieve. This is not to suggest that Treaties aren’t worth pursuing, but rather to highlight that they take time, even decades to come into effect. And even when they do – as demonstrated through the international examples – they are not always effective. As Yothu Yindi once more remind us, “words are easy, words are cheap”. Meanwhile, Indigenous people continue to suffer, experience poorer health and continue to die earlier than non-Indigenous Australians. Are these realities that really need discussion, negotiation, and compromise?

Voice to Parliament

The emphasis on a constitutionally enshrined Indigenous Voice to Parliament is prioritised, as it would not only grant constitutional protection, but would also facilitate the work towards Treaty. Despite this, we see politicians – across all parties – duck and weave with regards to a Treaty, or treaties. We hear words like “what if it fails”, “what if we get it wrong”, “what if there are issues”. The reality is negotiations for a treaty will face numerous challenges. At times things may be overlooked or need revising. This is part of the complex process of agreement-making.

The truth is, since Hawke 30 years ago, we could have stuffed it up and fixed it, not once, but many times. We could have had change and as a result we might have seen more Indigenous people making decisions. Seeing the structural and systems changes we so desperately need.

Permeating through both the calls for an Indigenous Voice to Parliament and the negotiations of treaty is a process of truth-telling. Makarrata is a Yolngu word associated with conflict resolution and one that translates to “come together after a struggle”. The Uluru Statement calls for a “Makarrata Commission” to supervise agreement-making and truth-telling between all levels of government and Indigenous peoples. The proposed Commission would enable parties to share information and work together.

Establishing an enshrined Indigenous Voice to Parliament however does not simply facilitate or allow truth-telling to occur, but rather is truth-telling in action. Truth telling without constitutional protection is simply a tokenistic symbolic gesture; a Wolf in Sheep’s clothing; a good “intention” without real action.

Voice, Treaty and Truth

Through Voice, Treaty and Truth, the Uluru Statement of the Heart offers the chance for real change. Its focus is on working within existing structures to create meaningful Indigenous representation within parliament. Professor Megan Davis, who was a member of the Expert Panel on Constitutional Recognition, and who grew up in Brisbane, puts it like this:

We do not have the luxury of walking away and giving up on structural reform. We have garnered enormous support, including from inside politics — just not enough support, yet. The logic of the reform, for the nation’s future, is irrepressible. Substantive, concrete reform is the only thing the nation has not tried … The conventional parliamentary system and its ancillary mechanisms have failed us. Yet we require that very system to endorse this change. We have no choice but to adopt strategies that engage the public.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart was a gift to the people of Australia.

It is a gift that the Australian people are demonstrating that they are willing to embrace.

The Centre for Governance and Public Policy shows that 71% of the public supported constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians back in 2017 when the statement was first released. Reconciliation Australia showed that this increased to 77 per cent in 2018 and 88 per cent in 2020. The Australian people are demonstrating that they want change. It’s now time for the government to allow them the opportunity to enact it through a referendum.

Time to Act

I ask readers, where do you want us to be as a nation in 30 years’ time? How do we want to be remembered? Will history repeat itself?

The Uluru Statement from the Heart and a constitutionally enshrined Indigenous voice to Parliament is a gift. A gift we owe to all our ancestors, and to our descendants.

It is my hope that you look back on today with pride and recall how members of your family signed the pledge for the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

That your descendants can see how you helped to enact change, rather than question why you, I, we didn’t do more and as a result are still fighting to make such changes a reality in 2051?

I ask you now:

- What are you prepared to do?

- What will you do?

- Who will you talk to?

- Who will you try to influence?

You can sign up to pledge your support to the Uluru Statement and its call for an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice to be enshrined in the Australian Constitution. In addition, make a submission to the Australian Government’s Indigenous Voice Discussion Paper by the 31 March and tell them what you think. The time for action is now!

If you carry out these actions, when you next hear the song Treaty, and you will hear it this year because it will be played as people reflect on it and celebrate its legacy, you can smile and feel satisfied that you did something to make a difference. Thank you.

Uluru Statement Supporters Kit

This is the week for action.

See a guide on making a submission here – https://ulurustatement.org/supporter-kit

Or see this submission generator – https://submission.ulurustatement.org/

Latest Comments